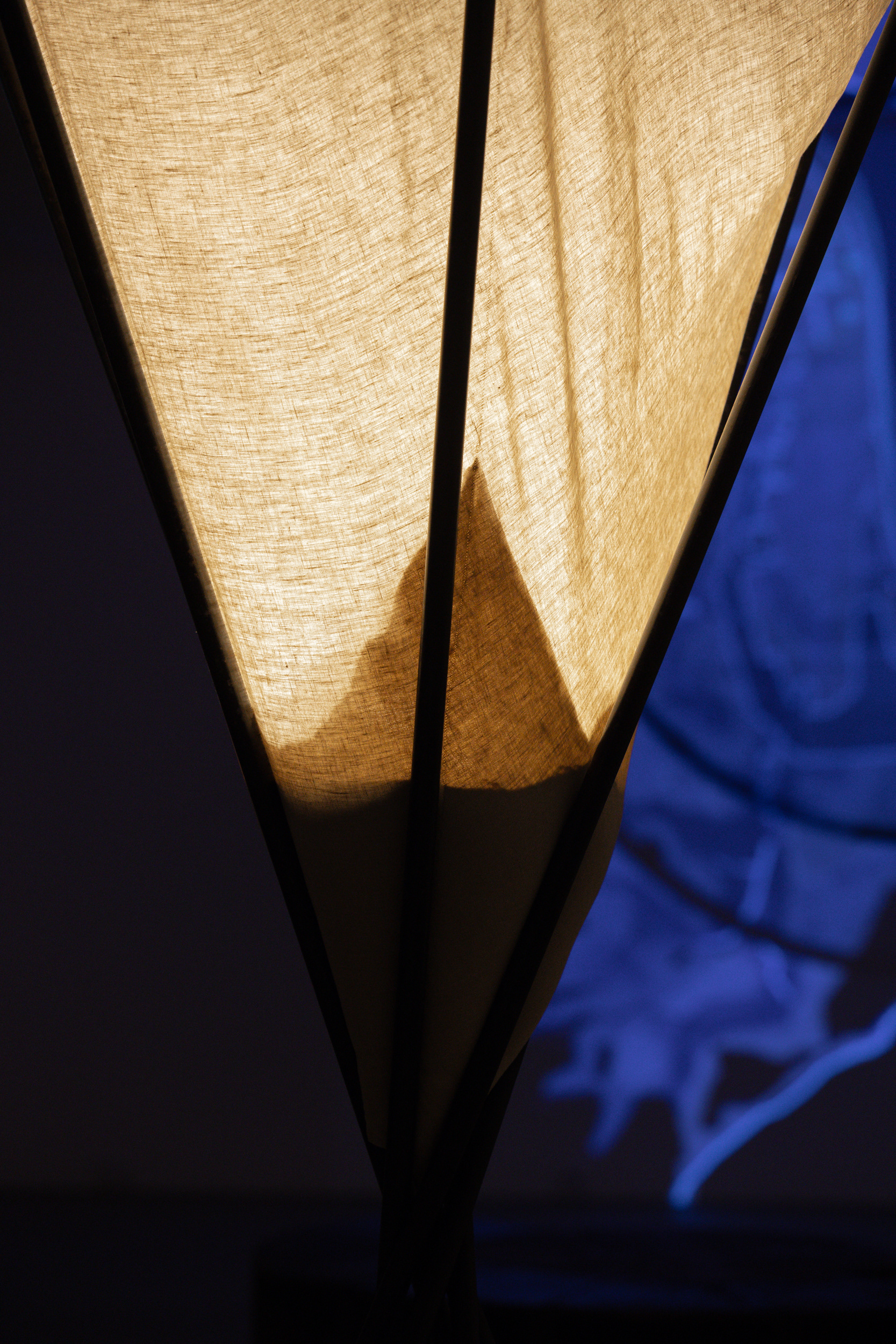

CANOE | RIVER PERSPECTIVE, 2024 | Shellie Smith (Awabakal, UoN)

The re-imagined canoe in Water Talks reclaims an important cultural form long central to First Nations presence on the river. More than a vessel, the canoe was a lifeline—enabling travel, trade, harvesting, and intimate relationship with the waterways that sustained communities. For the Awabakal and other coastal nations, it embodied reciprocity with Country: movement and nourishment held together with responsibility and care.

This work emerges from the reassembly of a previously dismembered canoe form, speaking to a wider act of cultural reawakening. Realised in collaboration with sculptor Julie Squires and led by Worimi man Luke Russell—together with the guidance and labour of many others—the canoe is now elevated on slender stands that evoke rushes, reeds, and spears. In this configuration, the viewer’s gaze shifts from that of the occupant to that of the river: we look up from below, as though the water itself is watching. This inversion recentres a more-than-human perspective, reminding us that Country is not only seen by us—it sees, feels, and holds us.

By repositioning the canoe in this way, the work invites a different reading of its form and story. This iteration allows the canoe to be encountered as a living cultural object—able to participate in varied forms, across places and times—so that its voice continues and expands. In becoming both conduit and witness, the canoe affirms that our stories, like the river, are not static but flowing still.

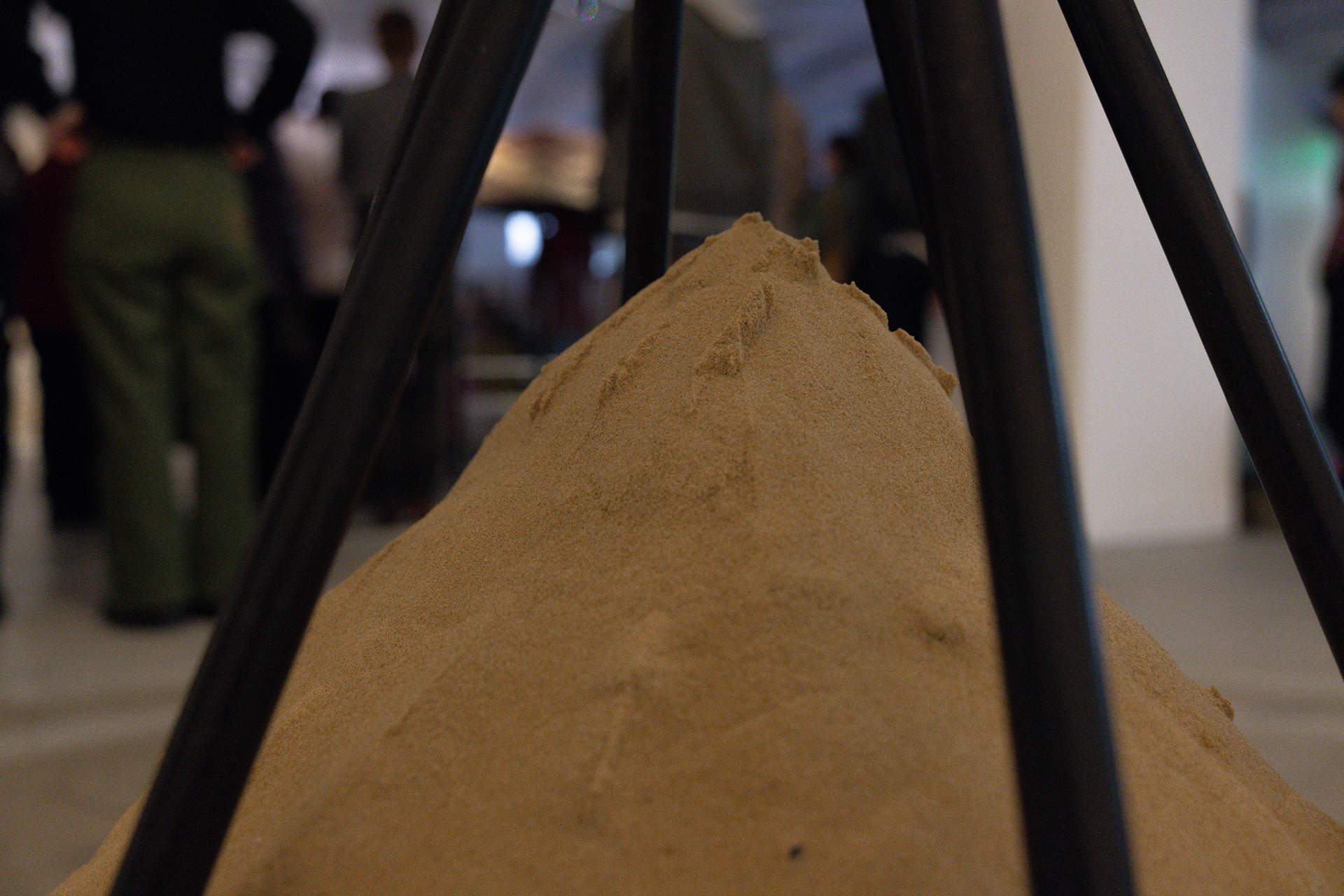

THE SAND STILL REMEMBERS THE WATER, 2025 | Irene Perez Lopez, Shellie Smith, Maria Cano Dominguez, Ananya Khujneri, ABEW—Tom Condurso.

Mild steel, linen fabric

Mild steel, linen fabric

This sand-based installation reflects on the shifting edge of the river and its deep entanglement with Awabakal culture, memory, and presence. It engages with the ever-changing form of Country—sculpted by the movement of water, sand, wind, and people—inviting viewers to consider how landscape holds story, erosion, and trace through time.

The work draws on the cultural and ecological dynamics of middens, riverbanks, and shorelines—threshold spaces shaped over time through First Nations occupation, ceremony, and sustenance. These edges are not static; they are living records, formed through layers of shell, sediment, and story. The installation honours these transitional zones as places of deep knowledge and ongoing transformation.

Sand and time is used here not only as a material but as a metaphor. It falls, flows, and settles. It responds to movement—of air, of water, of bodies—and is shaped accordingly. Viewers become participants in the work’s continuous reformation, their steps and interactions echoing the reciprocal relationship between people and place.

In a condensed timeframe – Hourglass, the installation offers an accelerated experience of natural processes: erosion, deposition, shifting form. It mirrors the way riverbanks reshape after each flood, the way middens grow through repeated gathering and return. These are not passive processes—they are evidence of long relationships with place, care for Country, and adaptation to change.

This work invites reflection on how we read and respond to the changing form of Country. It prompts questions about how we relate to the spaces where land and water meet, and how we carry forward knowledge that is shaped by movement, temporality, and touch. In doing so, it becomes not only an artwork but a moment of encounter—with the river, with memory, and with the living presence of First Nations knowledge embedded in the landscape.

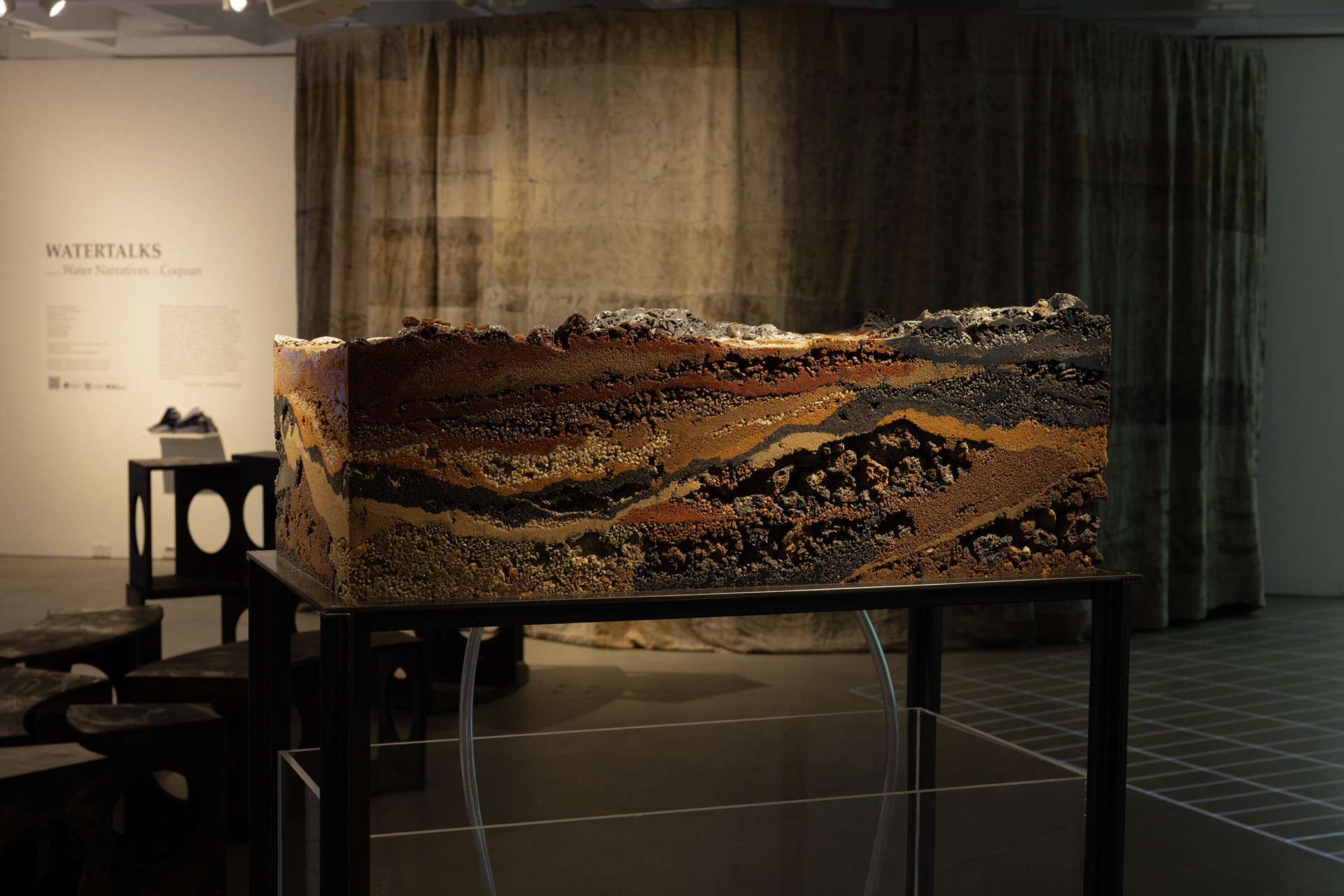

DEEPWATERS, 2025 | Irene Perez Lopez, Maria Cano Dominguez, Ananya Khujneri, Choi Cai, ABEW—Ethan Cranfield, Max Doran.

Mild steel, acrylic and encased layers of sand, aggregate, coal and subsoil.

Mild steel, acrylic and encased layers of sand, aggregate, coal and subsoil.

In the colonist view of the Aboriginal Country, water, land, soil, animals, and plants are endless resources to be extracted, hunted, and felled (Aplin & Parsons, 1988). Therefore, the River and its hydrological system are perceived not as a body of water or a living entity to be revered or respected but rather under a utilitarian gaze [...] or as a menace, an idea that dominates the thinking for much of the mid-20th century (Coyne et al., 2020).

Geomorphologically, the origin of the Valley dates back to the collision of the New England Fold Belt with the Australian continent during the Carboniferous-Permian period, approximately 300 million years ago. This collision created the Hunter, Liverpool, and the Great Dividing Range, shaping the river floodplain and coastal plains through various sedimentation phases, ultimately culminating in a final Quaternary sedimentation phase that shaped a vast coastal plain with an intricate hydrological system and rich coal deposits. Global climatic events, occurring between the Pleistocene and Holocene periods, led to rapid and dramatic environmental alterations approximately 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, including cataclysmic events such as rising sea levels and temperature increases, great floods, and earthquakes, which are captured in many Australian Aboriginal Dreaming stories (Maynard, 2000).

The Hunter region was one of the first areas outside of Sydney to be explored by the English, following the discovery of coal, which led to the drastic transformation of the Valley. The vast spatial and environmental metamorphosis initially accommodated the timber, limestone, and coal extractive industries, and today it is home to 41 coal mines owned by 11 producers, spanning over 450 km. In the Estuary, the shallow sandy waters gave way to heavy industry, including mining and metallurgy, and the accommodation of the largest harbour on the East Coast of Australia and the world’s largest coal port facility. Such commodification has privileged certain water systems and water management knowledge at the expense of neglecting or systematically erasing others.

The Water Management Act 2000 intensified manufactured scarcity by decoupling water licences from land titles, transforming water into an abstract, tradeable commodity. Under this legislation, water is distributed by priority rather than equity: in dry years, households and local agriculture face cutbacks while coal mines and heavy industry continue to receive allocations. These tensions are most acute in the Upper Hunter, where agriculture, industry, viticulture, and residents have long contended over scarce water resources (Albrecht et al, 2008)

DeepWaters visualise the magnitude of the impact of colonial practices on land and waters. A stand-alone geological section cuts an urban settlement – Singleton Heights; two hydrological bodies – the Hunter River, and one of its tributaries, the Wollombi Broo; and three mine sites – Mount Thorley – Warkworth, United-Project – BHP, and Rixs Creek – The Bloomfield Group, demonstrating the imbalances caused by human inhabitation, industrial and agricultural bounds on Country. To interpret the River’s eras, layers of sand, aggregate, subsoil, and water are encased in anthropogenic materials – disrupted soils and rocks and petrochemical subproducts, framed in mild steel produced in the Hunter.

NOT ALL THOSE WHO WANDER ARE LOST, 2025 | Nicole Chaffey (Biripi, Gathang language)

Natural dye pigments on linen

Natural dye pigments on linen

Ngathuwa Bilbala Watibiynguwa (I am painted with the trees)

“My practice is fundamentally nature-driven, examining the continuity of individual history, experience and memory through classical modes and materials: natural pigments, resins, oil, charcoal, and earth.

The eco-dyeing process strips creation back to its raw, natural origins and re-establishes an ancient lineage of colour extraction. It is an act of quiet alchemy; as protein, cellulose, metal, rainwater, and heat combine to yield subtle, unpredictable transformations as fabric receives the imprint of its environment, revealing marks which are, paradoxically, both ephemeral and enduring.

These actions are not simply about colour or surface, but about material memory – an intimate collaboration with the Country I walk and gather from, and the creation of a space in which to acknowledge the many thousands of feet and hands that came before mine, performing the very same.”

Nicole Chaffey is a Biripi woman living and working across the un-ceded lands of the Worimi, Wonnarua and Awabakal peoples in the Hunter Region. Her studio is situated on what was once an island, by the waters of Coquun (Hunter River), where she works across a range of media. Her works often delve into personal and collective histories, offering nuanced perspectives on the interwoven nature of past and present, as well as cultural resilience and contemporary identity.

These actions are not simply about colour or surface, but about material memory – an intimate collaboration with the Country I walk and gather from, and the creation of a space in which to acknowledge the many thousands of feet and hands that came before mine, performing the very same.”

Nicole Chaffey is a Biripi woman living and working across the un-ceded lands of the Worimi, Wonnarua and Awabakal peoples in the Hunter Region. Her studio is situated on what was once an island, by the waters of Coquun (Hunter River), where she works across a range of media. Her works often delve into personal and collective histories, offering nuanced perspectives on the interwoven nature of past and present, as well as cultural resilience and contemporary identity.

SALTWATER – NGAROKILIKO, 2025 | Shellie Smith

(Video Performance) MP4 files, Digital Screen, Powder Coated Steel

(Video Performance) MP4 files, Digital Screen, Powder Coated Steel

This video performance piece explores the deep connection Awabakal women have to salt water and its role in both protection and nourishment. It draws on colonial accounts of young women sheltering in the water during the early years of the penal colony at Coal River (Newcastle) to escape the violence of the settler/convict aggressors. For settlers and convicts, the ocean was a barrier, confining them to land and limiting escape. For my ancestors, the salt water provided refuge from their violence, offering safety, sustenance, and spiritual grounding.

The coastline of Awabakal Country has always been a source of strength and survival. It holds stories of resilience and resistance, shaping the lives of my people. For generations, the salt water has been a place of physical and cultural nourishment—a space to gather food, share knowledge, and connect with Country. My ancestors' relationship with the coast was one of reciprocity, respecting the ocean as both a protector and a provider.

Through this performance, I reflect on my own connection to the salt water. Having lived by the coast my whole life, I find comfort and belonging in its presence. Immersing myself in the ocean is a way of reconnecting with my ancestors and the stories they carried. The act of entering the water becomes more than a personal ritual—it is a continuation of an ancient bond that stretches back through time.

Through this performance, I reflect on my own connection to the salt water. Having lived by the coast my whole life, I find comfort and belonging in its presence. Immersing myself in the ocean is a way of reconnecting with my ancestors and the stories they carried. The act of entering the water becomes more than a personal ritual—it is a continuation of an ancient bond that stretches back through time.

The video captures this connection, weaving together past and present. It invites viewers to consider the complexities of salt water as a space of freedom and limitation, survival and oppression. It asks: How can we respect the coastal landscapes that hold these layered histories? What does it mean to inherit a connection to a place that has both sustained and sheltered our people in the face of colonial violence?

This work is a meditation on the enduring relationship between Awabakal women and the ocean—a relationship rooted in survival, culture, and belonging. Through it, I connect with my ancestors' strength and the ways they found protection and nourishment in the salt water. It is a story of resilience that continues to guide and comfort me today.

YARNABOUT, 2025 | Irene Perez Lopez, Maria Cano Dominguez, Ananya Khujneri

Traditionally, a “walkabout” is an Australian Aboriginal rite of passage that marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood. It provides a young person with the opportunity to practice and demonstrate the skills and knowledge required of their community’s adults. Upon successful completion, the young person is endowed with all of the rights and responsibilities of an adult.

walkabout.org

walkabout.org

The Yarning Circle YarnAbout is connected to a series of events that gather Indigenous and non-Indigenous Knowledge holders, community members, academics, scientists, and artists to participate in Yarns & co-design panels, aiming to build a collective narrative for the Coquun-Hunter River, Estuary, and Coastal Zone.

The Yarn Series is a collaborative co-design process that builds the cultural narrative and storytelling of rivers and river systems by leveraging Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge, enabling a community-led narrative. Yarns will empower stakeholders and knowledge holders through capacity building in the research narrative. The research deepens engagement with Indigenous methodologies, fostering cross-disciplinary collaborations and embedding Country-led practices into future academic and artistic work, enriching cultural understanding and environmental conservation and stewardship approaches. This process strengthens local expertise and ensures Indigenous perspectives shape the narrative.

The Yarns will help to reflectively create new knowledge and outcomes related to the exhibition/s through a collaborative process, enabling an Indigenous researcher to build capacity and skills in research methodologies, exhibition development, and cultural

storytelling.

storytelling.

Let me start by saying that I do not claim to be an academic.

But I know what it is like to sit by a river.

I know what it feels like to watch water pass by, maybe never to be seen again.

Water lost around the bend

and then

down somewhere, somewhen, unseen.

Forgotten

Even tidal streams don’t seem to bring back the same water twice.

But the River stays the same…

Yes, they change.

They grow larger, smaller. The slight rearrange.

But the river remains.

How could they not?

A living entity?

These anthropocentric misunderstandings, The Forgettingness…

Trees to be cut down, mangroves cleared, animals and peoples hunted into fear of oblivion;

Transported stories and Transported people these “Tamers of Nature”.

As if you yourself were never part of nature in the first place.

Rivers now used as commodifiable resources instead of family members to be taken care of. Kin and country? No …

Kin IS COUNTRY!!

You see, I know what happened. I’ll tell you a secret.

“You forgot your story” – That Earth Law that they talk about.

Our old ones taught me of such a lore.

One of reciprocity,

But I know what it is like to sit by a river.

I know what it feels like to watch water pass by, maybe never to be seen again.

Water lost around the bend

and then

down somewhere, somewhen, unseen.

Forgotten

Even tidal streams don’t seem to bring back the same water twice.

But the River stays the same…

Yes, they change.

They grow larger, smaller. The slight rearrange.

But the river remains.

How could they not?

A living entity?

These anthropocentric misunderstandings, The Forgettingness…

Trees to be cut down, mangroves cleared, animals and peoples hunted into fear of oblivion;

Transported stories and Transported people these “Tamers of Nature”.

As if you yourself were never part of nature in the first place.

Rivers now used as commodifiable resources instead of family members to be taken care of. Kin and country? No …

Kin IS COUNTRY!!

You see, I know what happened. I’ll tell you a secret.

“You forgot your story” – That Earth Law that they talk about.

Our old ones taught me of such a lore.

One of reciprocity,

Both taking and giving

And giving and taking

And taking and giving.

Those living, tidal waters.

Taught us.

That same LORE too.

Leave it up to us to think that we can change the way that water knows us.

Are we not made up of her?

The rivers will dry,

The rivers will punish,

And again, we will centre ourselves so that we can claim that “we” were the reason that it all happened.

Yet when all is said and done, there will be less done than said.

And the rivers will decide to give their water back to the tides.

All of this, because they have been dispossessed of their relations, not just the other way round.

The rivers know. They have always known.

They will retake their true image.

You may not believe me, but they are already their true image.

And if we do not act now;

if we do not sit by their side,

if we do not listen as the Water Talks.

It will not be the water, but we who will be lost around the bend

and then

down somewhere somewhen unseen.

Forgotten