COQUUN – MYAN FLUID IMAGINARIES, 2022-25 | Irene Perez Lopez

Research Ananya Khujneri, Choi Cai, Jye White, Dr. Callum Twomey.

Videographer Adviteeja Khujneri

Immersive video projection - MP4 files

The Koori, or Goori, knowledge of the Hunter Valley extends back to the times of the Dreaming. The Hunter River is known as Myan by the Wonnarua people, and Coquun by the Awabakal and Worimi, presumably connected to the name for water Ko-ko-in (Dyall, 1971). Coquun-Myan is the biggest river in the Hunter Bioregion and flows along the confluence of two geological basins, the foreland Sydney Basin and the New England Fold Belt (Roy, 1996); and, four Koori - Aboriginal Lands – Awabakal on the Southbank of the River, Kattang speaking Worimi on the Northern bank, and Gringai and Wonnarua,or Hunter River tribe, inland the river.

The River has a broad coastal plain with a complex hydrological system, including an alluvial valley dotted with a vast freshwater alluvial swamp, such as Burraghihnbihng or ‘the Big Swamp’ at Hexham, comprising river channels, levees, tributaries, and the Hunter Wetlands National Park, listed under the Ramsar Convention. Early colonial chronicles describe exuberant riverbanks, short tender grasses clear of trees, and dense eucalypt-dominated forests with “immense gum and iron-bark trees, giant cedars and graceful wattles” (Albrecht, 2000). The impact of two centuries of economic activity on the river basin's ecosystems is evident, with over 85% of native vegetation lost, only 40% of forested areas retained, and 99% of riparian vegetation removed, resulting in bank erosion, turbidity and loss of multiple native species (Albrecht, 2000; McVicar, 2015).

The history of the Coquun-Myan Hunter River is marked by extremes, whether due to excessive water or insufficient water. Patterns of severe flooding shaped new eras of the River basin, while engineered flood controls further altered its hydrology by replacing natural levees with hard edges and depriving the river of new layers of alluvial soil. Urbanisation compounded these impacts, with lowlands and floodplains cleared and built upon, and tributaries channelised with concrete, disrupting water systems that once nourished wetlands, swamps, and lagoons. The environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht emphasises that flooding is a significant disturbance with immediate catastrophic ecological impacts, although the Hunter River has historically rebounded from such shocks. Its biodiversity is dependent on regular disturbances to maintain richness and complexity.

The history of the Coquun-Myan Hunter River is marked by extremes, whether due to excessive water or insufficient water. Patterns of severe flooding shaped new eras of the River basin, while engineered flood controls further altered its hydrology by replacing natural levees with hard edges and depriving the river of new layers of alluvial soil. Urbanisation compounded these impacts, with lowlands and floodplains cleared and built upon, and tributaries channelised with concrete, disrupting water systems that once nourished wetlands, swamps, and lagoons. The environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht emphasises that flooding is a significant disturbance with immediate catastrophic ecological impacts, although the Hunter River has historically rebounded from such shocks. Its biodiversity is dependent on regular disturbances to maintain richness and complexity.

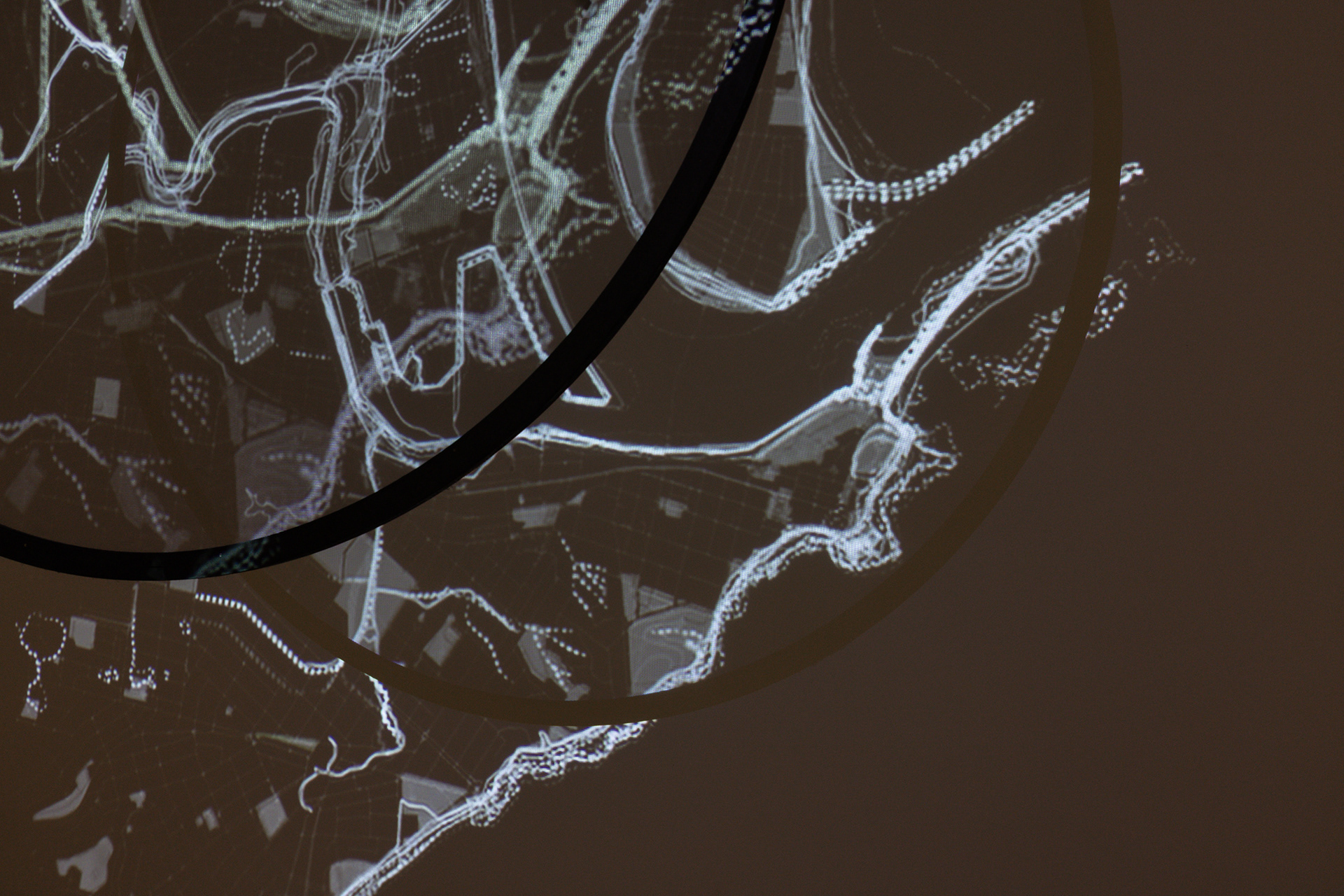

Dynamic projections illuminate the gallery, offering a sensory encounter with the Coquun-Myan’s Transformative Eras. This immersive experience, animated in a slow-moving video, presents a multiscale imaginary water-scape series that documents the changes inscribed in the river’s body. The projection spans a large diagonal portion of the gallery, documenting the Coquun’s geomorphic and hydrological transformations and centring visitors in the evolving riverine landscape, promoting interaction between visitors and the Coquun-Myan story.

DISTURBED WATERLANDS, 2022-25 | Irene Perez Lopez

Research | Ananya Khujneri, Choi Cai, Jye White, Dr. Callum Twomey.

Videographer | Adviteeja Khujneri

Video Projection - MP4 files

Research | Ananya Khujneri, Choi Cai, Jye White, Dr. Callum Twomey.

Videographer | Adviteeja Khujneri

Video Projection - MP4 files

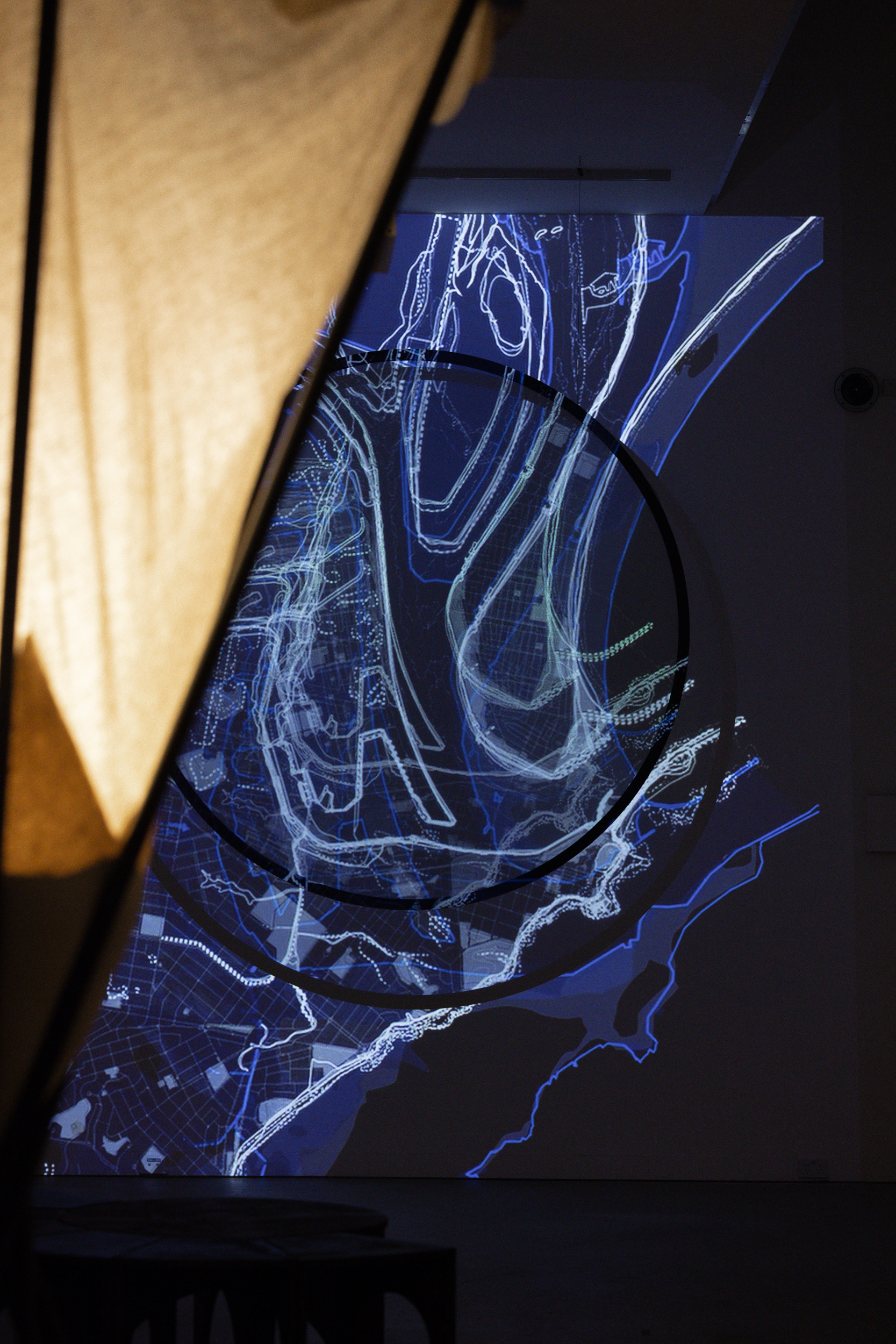

A cartography through time is being constructed in search of the original water landscapes in Mulobinbah - Newcastle. Spanning thousands of years, the timeline reaches back to geological ages, with the first map in the series estimating estuary conditions around 120,000 B.C., and forward to 2,100 A.D., into a speculative future governed by the unpredictable forces of climate change.

Historical maps and surveys of Newcastle and the Coquun-Myan River are prolific in revealing places, histories, and cultures across time. While originally created for surveying purposes crucial to the maintenance of state power (Harley, 1988: 287), they now stand as visual testimony to the processes that have irrevocably altered Awabakal and Worimi Country. Maps chart the spatial legacy of power, 'growth’, land and water management through the exploitation, extraction, transportation, and accumulation of coal, timber, and goods along the Coquun-Myan River and its estuary.

Visually tracing hydro-spatial narratives over time reveals hidden, erased, and active waterscapes in the Coquun-Myan Estuary. The reconstruction of such a narrative aims to reconnect place and water as complex cultural, social and more-than-human geographies. By making visible the spatial mutation through time, this investigation uncovers new and unexpected relationships between space, community, and environment while unfolding past, present, and future threats to inhabitation.

The video superimposes, compares, and interprets these changes to connect space, time, culture, and environment. The mapping visually articulates the interplay of diverse forces, including historical and local events, Indigenous and colonial toponymy, the hydrological and geographical patterns and imprints, economic drivers of land reclamation and speculation, and extreme climate events threatening the estuary, which hold direct implications for current and future urban sustainability and security.

The film presents a critical analysis through time to respectfully discover ‘what has always been present and will always remain’, building on Potter’s (2020) principles of Country, not as a place of ‘nature’ that preceded colonial urbanisation, but as perpetually present, a sovereign place that organises life and cannot be superseded or erased, despite the effort of settler-colonial urbanism. In other words, the work presented here claims the sovereignty of the Coquun-Myan-Hunter River and its water ecosystems as a living system and a key actor in any economic, cultural, or spatial actions (Tănăsescu, 2020). The river, its water system and logic should be recognised as active stakeholders in its management, fostering a greater sense of engagement and belonging